Why I'm live streaming the creation of a scientific paper

Watching other people play computer games has become phenomenally popular. If you think this sounds absurd then you're probably over the age of thirty or don't have any kids.

This past June alone almost a billion hours of streams were watched on Twitch, the leading live streaming platform. E-sports, which is another term for video game competitions, are even now competing with conventional sports when it comes to viewer numbers and prize money. This is wild.

In parallel to e-sports, there’s a smaller community of people that live stream their coding and writing. I've tried live streaming a few R coding sessions myself, which were daunting but fun experiences. But these live streaming sessions felt a little artificial, as I was demonstrating coding tasks and datasets that I'm fairly familiar with.

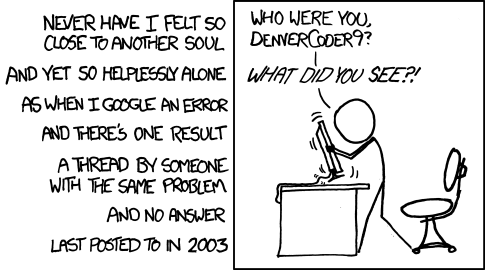

This isn't how science works. Datasets are messy, you're often learning new skills on the fly, and you're always wrestling with cryptic error codes.

You only tend to hear about people successes in academia. But considering that success rates for most grants and paper acceptances in prestigious journals are hovering around 10-20%, someone out there must getting rejections—we're just not hearing about it. It can be immensely reassuring to discover that your mentors and peers experience failure, but this kind of disclosure is rare.

Outright successes and failures are just the two ends of the spectrum, which punctuate our careers on the odd occasion. The reality is that a typical day in academia can be quite banal. You don't often see tweets about these run-of-the-mill of days, despite their ubiquity.

Some news... Very pleased to announce that today was just a normal day. I spent 20 minutes figuring out whether “latest_version.doc” or “latest_MS.doc” was the latest version, reset my online manuscript submission password, and googled “R stats chi test” for the umpteenth time

— Dan Quintana (@dsquintana) May 11, 2019

Now that the technology is available and that there seems to be some interest in watching other people work, I want to demonstrate what writing a paper is really like by live streaming the creation of one.

There are three reasons why I want to do this:

1. To offer a peek behind the curtain

There’s a lot of mystery surrounding how to write a scientific paper. Young scholars are just expected to learn how to pick up this difficult skill. Sure, there are a few books out there giving pointers, but the best way to learn something is to watch someone else do it.

When looking at the productivity of some senior scholars, it can seem like that they simply sit down and a final draft is revealed to them. But there are multiple revisions that go into a single paper. Some of my bigger papers have gone through at least twenty versions before submission.

Of course, I don’t think the way that I write papers is the best way, but it’s certainly one way.

I enjoy making tutorials about R and scientific writing and think this is an important service to the community as an early-to-mid career scholar, but these things take time. By live streaming the work that I’m already doing, I'll be making better use of my time, which is especially important to me now that I'm a parent.

2. Accountability

There aren't many better ways to get a task done than knowing that people are watching you. I'm very fortunate to have my own office now, but when I was a PhD student I shared offices. I knew that no one was policing how much I was working as everyone has their own stuff to do, but the knowledge that they could see what I was working on was enough to limit my procrastination.

I want to see whether this live streaming will actually help me work more efficiently knowing that people can be watching.

It’s easy enough to block access to social media sites for given blocks of time, which I already do using the SelfControl app. But what’s harder to monitor is the kind of work that’s referred to as ‘false hustle’. This is the stuff that feels like work, but isn’t really getting you closer to your main goals. You know, stuff like updating your CV or aimlessly reading papers.

I have no idea if people are going to watch this stream, and I frankly don’t really care. I'm more interested to see how this extra level of accountability will influence my work.

3. To improve how I write manuscripts and code

I want to get better at writing and definitely get better at coding. When it comes to coding, I've got a grasp of the basics but I know my code is inefficient and often has redundancies. I gotten some great tips from people who've watched my live streamed R coding sessions that save me time.

loving the ggstatsplot package. The subset function is also useful for filtering data (e.g., t.test(mass ~ gender, data = subset(sw_nj, gender == "male" & gender == "female"). Cool vid! 👍

— Jonatan Ottino (@jottinog) June 5, 2019

When it comes to my writing, I'm interested to see whether I can get some real-time (or close to real-time) comments as I write my manuscript. Co-authors can offer some great feedback, but they often share our the biases that are easy to miss. I'd much rather find out there' something wrong with my manuscript during the writing phase than when it's already been published.

The paper topic

I think the current push for open data is the right way forward, but there are many circumstances where it's not possible to share your data due to privacy concerns. This is especially an issue when working with populations with rare disorders in smaller cities, whereby data is more easily identifiable.

There is a clear trade off to be made between the utility of sharing data and disclosure risks. Of course, if we were to share all of our data this would be incredibly useful for science, but blanket data sharing would be at the cost of disclosing personal information.

With this in mind, I've been exploring ways that data can be shared while still respecting the privacy of research participants. I recently came across the synthpop R package, which creates a synthetic version of your dataset while retaining the same properties and relationships between variables. Synthpop seems to offer an ideal solution for increasing the utility of shared data without sacrificing disclosure risk.

There are a few reasons why I'm really interested in synthetic datasets. First, readers and reviewers can better understand the data, as they can explore dataset properties such as distributions, variance, and outliers. Second, other researchers can explore the data and fit hypothesis-generating models, which can be verified by the original authors using the real dataset. Third, synthetic datasets can be used to accompany analysis scripts, which can be difficult to follow without the dataset. Finally, the publication of a synthetic dataset would incentivize scholars to carefully audit their analysis scripts, given that others might inspect it and attempt to recreated the published analysis.

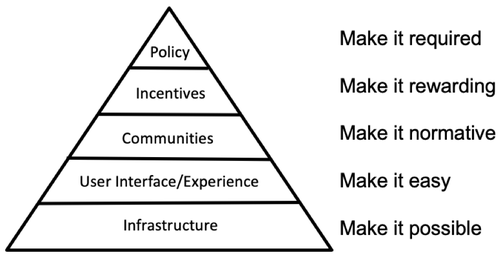

Culture and behavior change is hard. The Center for Open Science recognizes that an important step for the wholesale adoption open science practices is to make it easy.

My plan is to demonstrate how to create synthetic datasets and validate them against the original datasets. Synthpop has been used to create synthetic datasets in the biobehavioral sciences before, but right now there's no accessible guide to creating these datasets in the context of biobehavioral science.

In this paper, I will focus on behavioral oxytocin research, considering that's my field of study and that datasets from oxytocin studies are rarely shared. I'm planning on using 2-3 datasets that are already open. I might also introduce missing data, outliers, and skewness to examine the robustness of the methods. As well as the R coding, the stream will also include the write up of the manuscript.

I hope to live stream twice a day (mornings and afternoons) during the weekdays for about an hour each session beginning July 22. I might do more or I might do less, depending on how my day is going. I'll use both Twitter and Twitch for streaming and then post the video afterwards on my YouTube channel.

Wish me luck.