Recalibrating research practices can help establish trust in oxytocin research

I was in the third year of my undergraduate degree in 2005 when I first heard about the hormone oxytocin. That year, an article was published in Nature reporting that a single administration of the oxytocin increases trust in other people. What’s more, this increase in trust wasn’t due to oxytocin improving mood or reducing anxiety.

In this study, Michael Kosfeld and collegues asked participants to play a decision-making game using real money, which indexed the participant’s willingness to trust others. In this game, participants are randomly assigned to play as an investor or a steward. Both investor and steward begin with the same amount of money, but the investor can send money to the steward, who can triple the invested amount. But it’s up to the steward to how much money they send back to the investor.

Let’s illustrate how this game works with a $10 starting amount. If the investor doesn’t trust the steward to return any money, they’re better off keeping all their money. This means that the steward will also end up with $10. If they have some trust in the steward and send $5, the will tripled to $15. The steward now has $25. The most equitable response in this scenario is for the steward to send back $7.50, so that both will end up with $17.50. The best outcome for both investor and steward is for the investor to send the the entire amount of $10. The steward would triple this to $30, and both players could walk away with $25. But of course, the steward can choose to keep all the money and walk away with $40, a scenario that the investor will have at the back of their mind. Ultimately, the more money the investor shares, the greater trust they have in the steward.

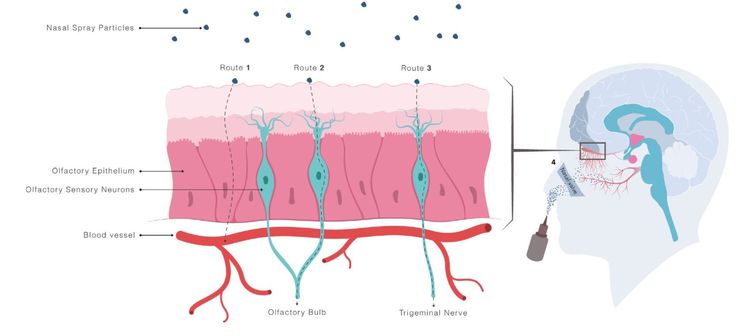

Before playing this decision-making game, participants were randomised to receive either intranasal oxytocin or placebo. Administering oxytocin and expecting a change in trusting behaviours wasn't a hypothesis that appeared out of thin air. This was on the back of over a decade's worth of animal research demonstrating oxytocin's role in affiliative behaviours. This has been shown using both gene knockout studies, in which rodents without the oxytocin gene demonstrate impairments in affiliative behaviours, and with oxytocin administration studies.

Kosfeld and co-workers reported that participants who were randomised to receive oxytocin before playing the game transferred more money compared to those given placebo, suggesting that oxytocin increased how much trust the investor had in the steward.

This remarkable finding captured my attention. Oxytocin is an evolutionary ancient hormone, whose ancestral form is found in fish, reptiles, and worms, yet it also seemed to influence complex human cognition.

But while this study was the spark that ignited a new research field, serious doubts began to emerge regarding the reliability of these results. A decade after the original report, the several attempts to replicate the original finding were synthesised in a meta-analysis, which concluded that intranasal oxytocin does not increase trust. However, these studies were only conceptual replications, as none of them used the same methods as the 2005 study (they only evaluated the general concept of oxytocin’s role in trusting behaviours). The sample sizes in these conceptual replication studies were also relatively small, like the original study.

Another crucial departure in study design in these replications from the original study was the use of social contact before participants played the game. In the original study, there was brief contact between participants session before testing, whereas none of the replication studies included this feature. This is seems to be an important factor, as past research using a similar task found that intranasal oxytocin increases coordinated behaviours, but only if participants had minimal social contact before commencing the game.

Most intranasal oxytocin studies also have small samples sizes, which means that the results are less likely to replicate in subsequent experiments. In the meta-analysis I mentioned earlier that included seven studies, the average sample size for the oxytocin groups was 29 for the oxytocin group and the 26 for the placebo group.

It was against this backdrop of small sample sizes and indirect replications that Carolyn Declerck and colleagues, which included one of the authors from the original paper, designed an experiment that was recently published in Nature Human Behaviour. This study was a direct replication of the original trust study, as it included minimal contact before the game. They also included a condition with no contact between participants before the game, to assess if this made a difference regarding the effects of oxytocin. Importantly, they also recruited a large sample of participants (n = 677).

The study was submitted as a Registered Report, which is an emerging publication format accepted at over 250 journals (see the list of journals here) that is peer-reviewed in two stages. In Stage 1, the study is reviewed before the data collection and assessed on the merits of the research question and the study design, such as the appropriateness of the sample size and statistical tests.

After the study passes Stage 1, it is granted in-principle acceptance, regardless of the results. In other words, even if the results aren't statistically significant the study will still be published. After collecting the data and reporting the results and conclusions, the authors submit Stage 2 of their report. Here, the reviewers and editorial team check the consistency of the analysis with the original proposal and that the conclusions match the data. Crucially, the reviewers cannot critique the study design at Stage 2, as they already approved it at Stage 1.

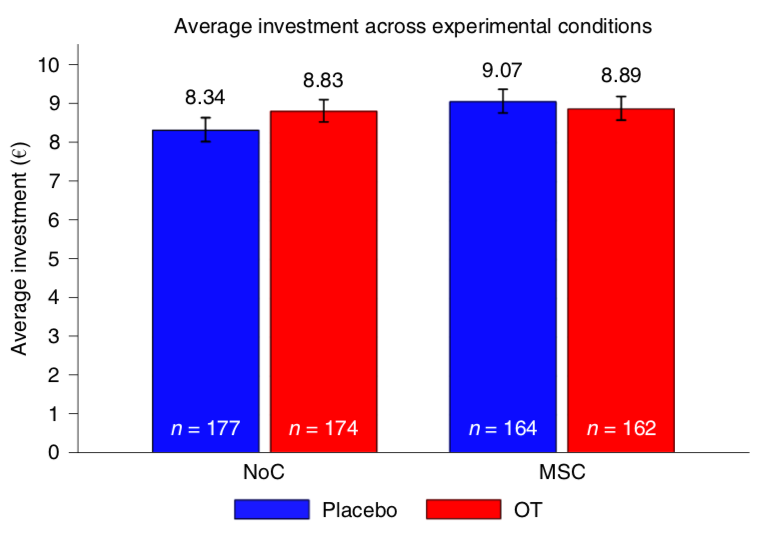

The main hypothesis specified before data collection was that intranasal oxytocin would increase trusting behaviours for those that had minimal social contact (referred to as "MSC" in the figures). However, after analysing the data there was no support for this result.

It is typically difficult to interpret a non-significant result, other than a failure to reject the null hypothesis, when using conventional null hypothesis significance testing. This is because there's no way to tell from a p-value alone whether a non-significant result supports the absence of a meaningful hypothesis or is due to an underpowered study.

There are two emerging approaches for understanding non-signifiant results. Equivalence testing provides a means to reject an effect size that is practically or theoretically meaningless (see this paper for an example of equivalence testing in oxytocin research). Bayesian hypothesis testing provides a test of the relative evidence for two competing hypotheses—such as a null and alternative hypothesis. One appeal of Bayesian hypothesis testing is that it provides an easy-to-interpret result—how much more evidence is there for one hypothesis over another?

In this study, the authors used Bayesian hypothesis testing. For the main hypothesis that oxytocin increases trust in the minimal contact condition, there was over ten times more evidence for a null model relative to an alternative model. This is fairly convincing evidence for the null hypothesis, and the kind of information you can’t glean from a non-significant p-value.

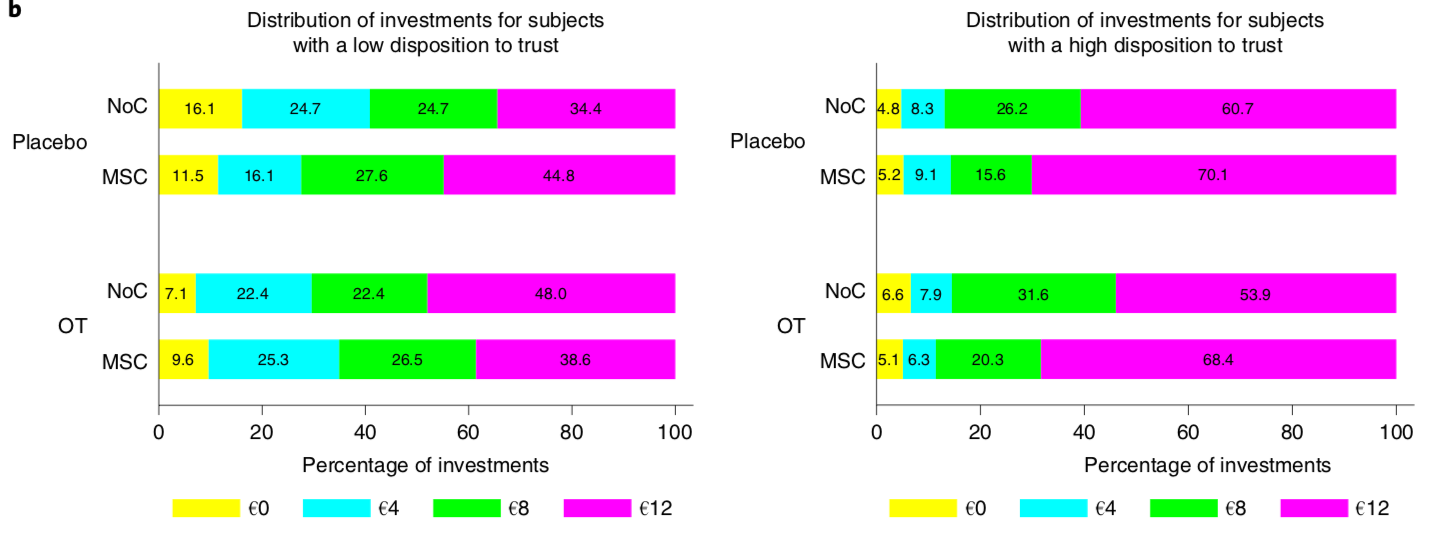

There's a wide spectrum how of much individuals trust other people. This is reflected in the data when you look at the behaviour of those administered placebo, as some investors kept all of their money, while others gave everything they had to the steward, expecting a return.

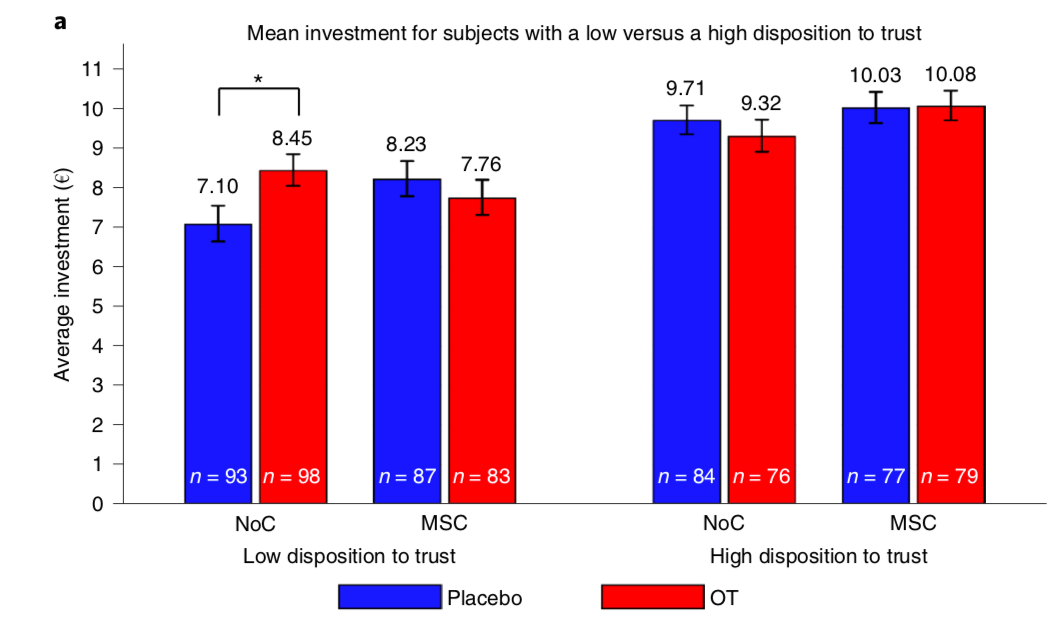

Around two weeks before the actual experiment, participants filled out a series of online questionnaires, which included a measure of their trust disposition. As shown on the right panel of the image below, over 50% of investments from those with a high disposition to trust were at the €12 limit—they simply couldn't invest more money.

An exploratory analysis of the data revealed that that individuals with a low trust disposition who had no contact with other players before the decision-making game (referred to as the "NoC" group in the figures) behaved in a more trusting manner after oxytocin treatment.

The fact that people with a low disposition to trust ended up investing more money is plausible. However, this was not in the original analysis plan proposed at Stage 1. The analysis only became apparent when looking at the data, which revealed ceiling effects in terms of how participants behaved.

As this result was explicitly labelled as an exploratory finding, this provides a healthy dose of skepticism as to whether this finding will replicate. But it also provides a clear path forward for future research. This result is also a reminder that you're free to report exploratory analysis in Registered Reports, but you just need to label them as such.

Low sample sizes and a lack of transparency have been a considerable issue for intranasal oxytocin research. This study provides an example as a way forward for the field to increase trust in its findings. The data is publicly available, which means the results can be verified. A specific hypothesis and analysis plan was specified before data collection, which is crucial for the replication of results. There was also a means to falsify the hypotheses.

Oxytocin is a complex hormone that we’re only beginning to understand, despite the discovery of its effects over century ago. To be honest, I’m half-expecting a few lazy tweets declaring that this study heralds the demise of intranasal oxytocin research. But as the authors state, the results only have implications for the general hypothesis that intranasal oxytocin increases trust, not other areas of social cognition. In fact, increasing evidence suggests that its psychological effects are not even exclusive to social cognition, but that it’s also involved in non-social cognition.

Improving research practices in the field, as demonstrated by this study, will help researchers more quickly understand the role of oxytocin in physiology and behaviour and save resources by limiting the pursuit of hypotheses that are likely to be dead ends.